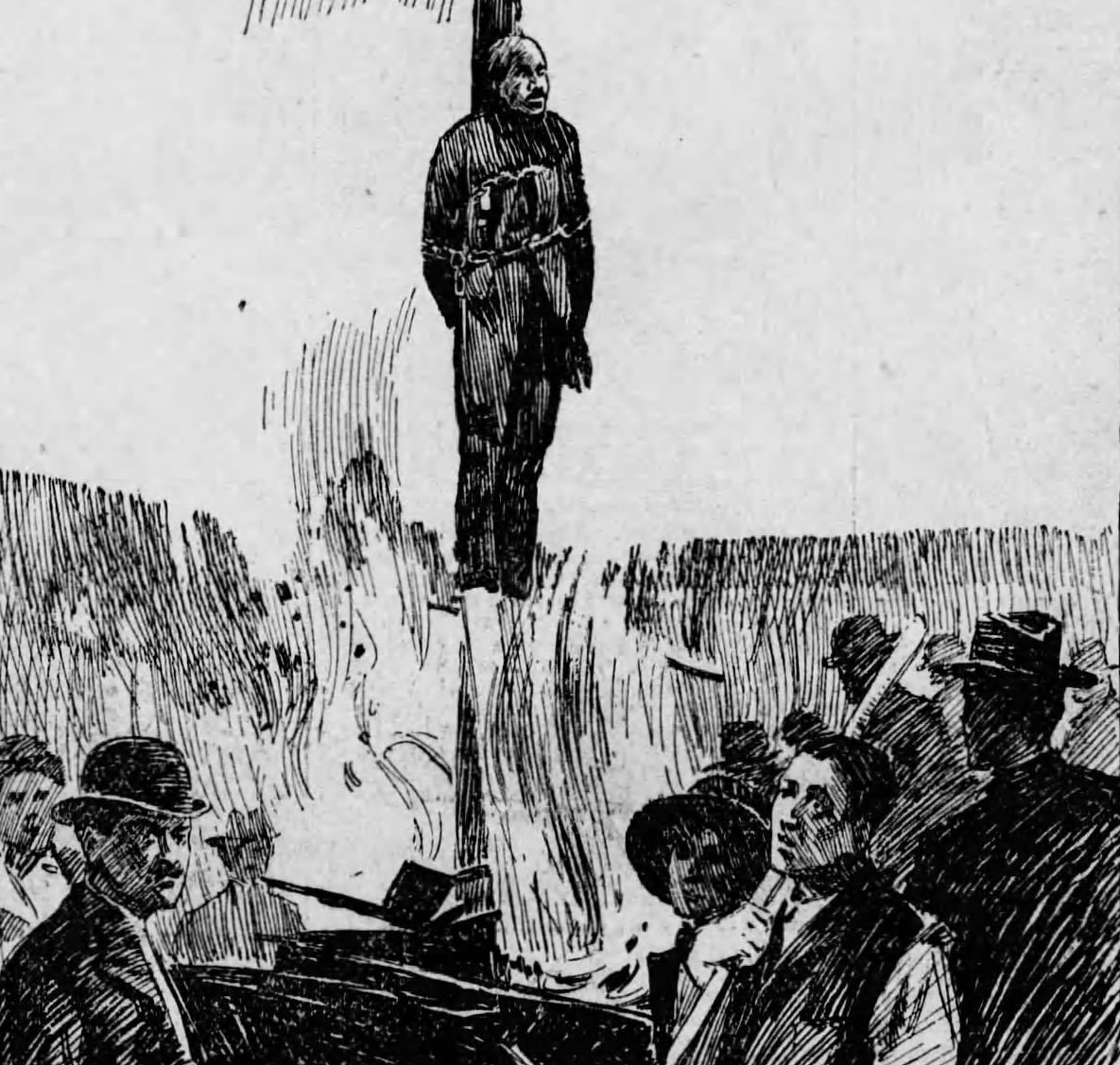

10,000 Lynch Negro At The Stake In Downtown Tyler, TX

1895 - WE REMEMBER HENRY HILLIARD

The Lynching Of Henry Hilliard

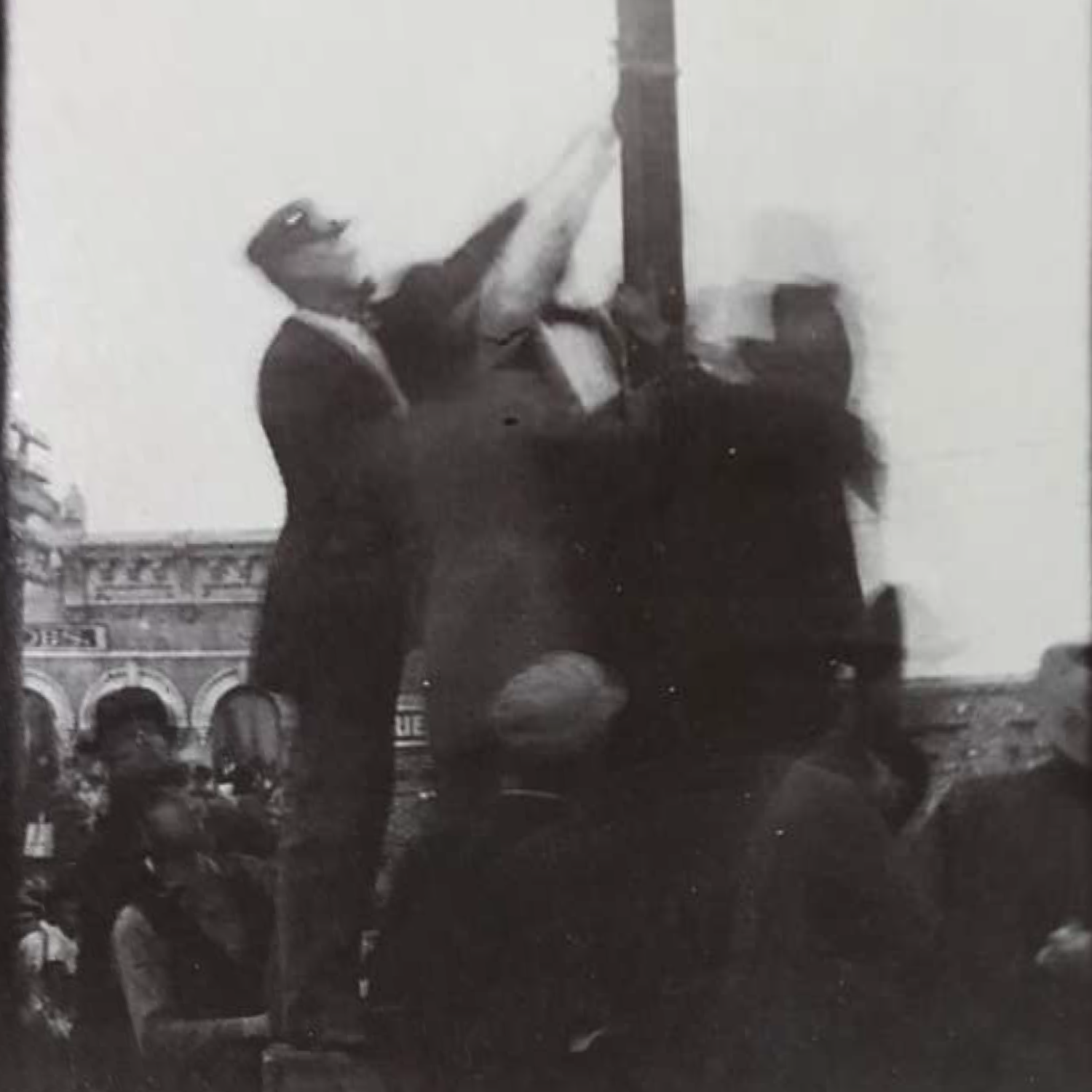

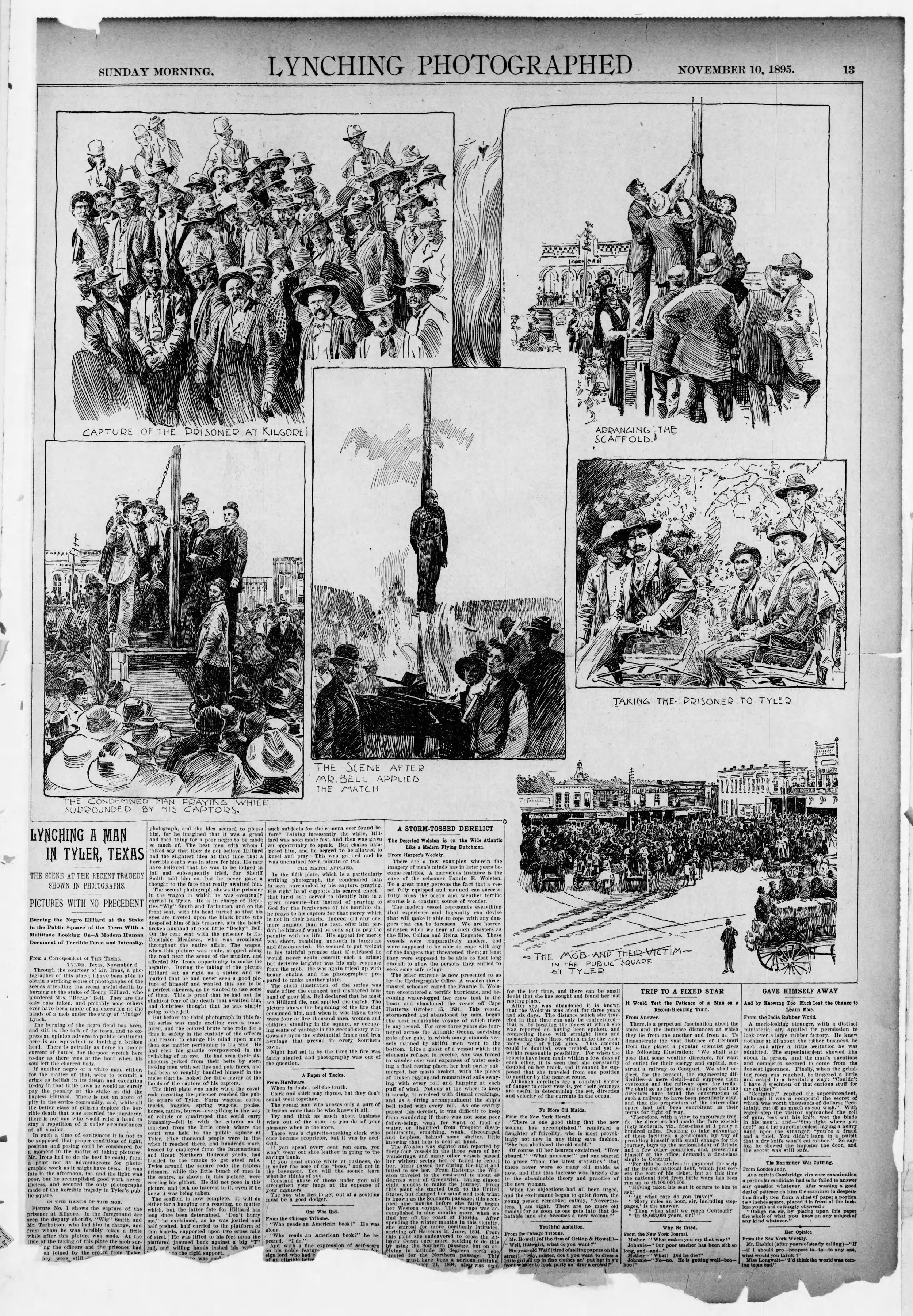

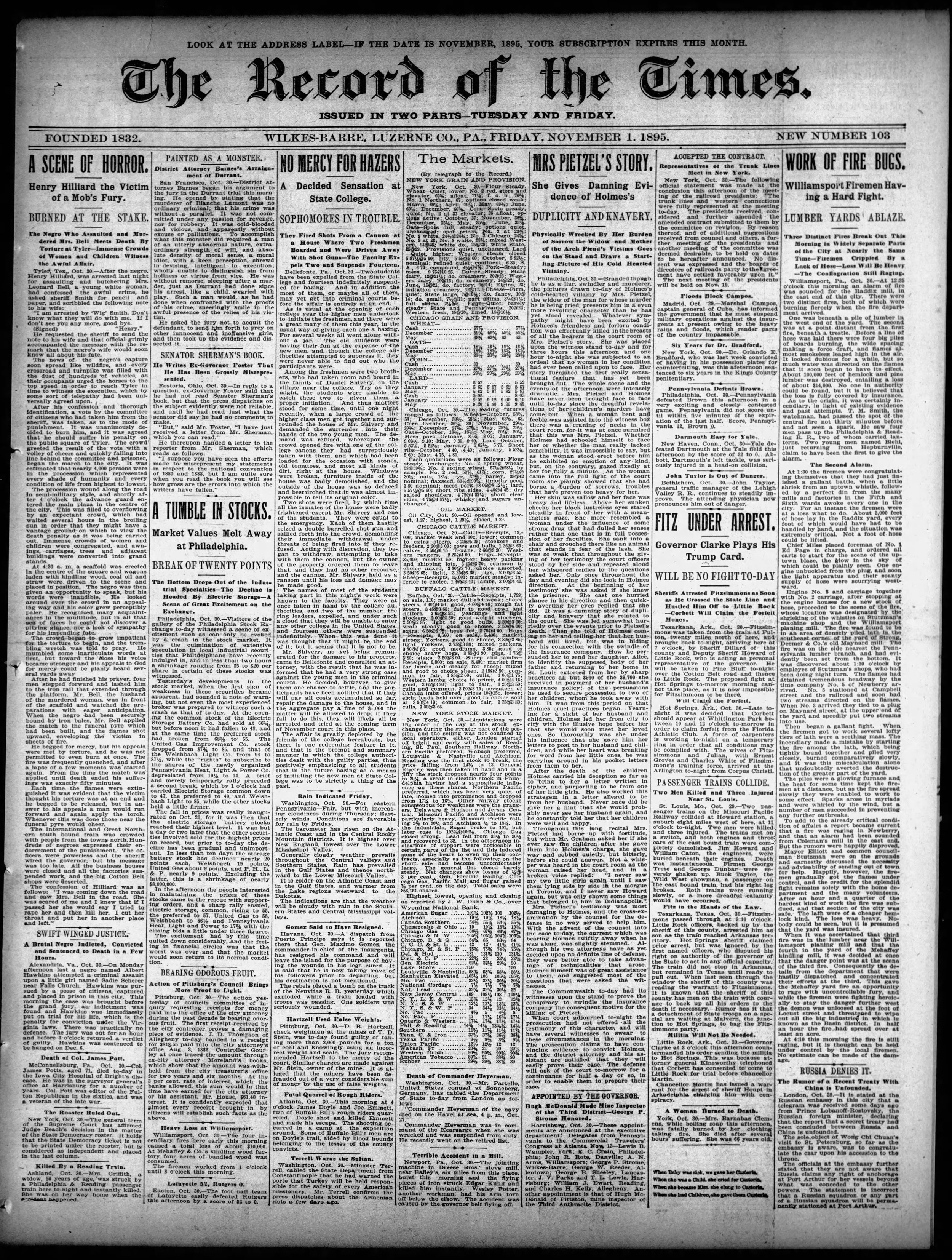

Two years after Henry Smith’s infamous torture by a lynch mob in Paris, Texas, Henry Hilliard (aka Robert Denson Hilliard) was burned at the stake in downtown Tyler. The lynch mob numbered an astonishing 10,000 people. One account called it the Tyler Tragedy. On October 29, 1895, newspapers throughout America began reporting on the gruesome Tyler, Texas lynching of Hilliard, including the Fort Worth Daily Gazette, the Gainesville Daily Hesperian, and the San Antonio El Regidor.

Hilliard was suspected of the rape and murder of the nineteen-year-old wife of local farmer Leonard Bell. After fleeing east, Hilliard was discovered and arrested early the following day near Kilgore, Texas by Smith County Sheriff Wig Smith.

How they knew what the rapist-murderer looked like was nothing short of magic. The only witness to the crime was dead.

On their way back to the crime scene, Sheriff Smith and his party were followed by over 20-armed Bell supporting vigilantes. Upon arriving at the Bell farm, law enforcement encountered an additional two thousand men who then forcefully took Hilliard into their own custody. Hilliard then supposedly confessed, which would have been under duress, saying, “I was coming down the road and saw Mrs. Bell in the road. She was afraid of me, and I knew that if I passed her, she would say I tried to rape her, and I concluded that I would rape her and then kill her. I cut her throat and then cut her in another place and left.”

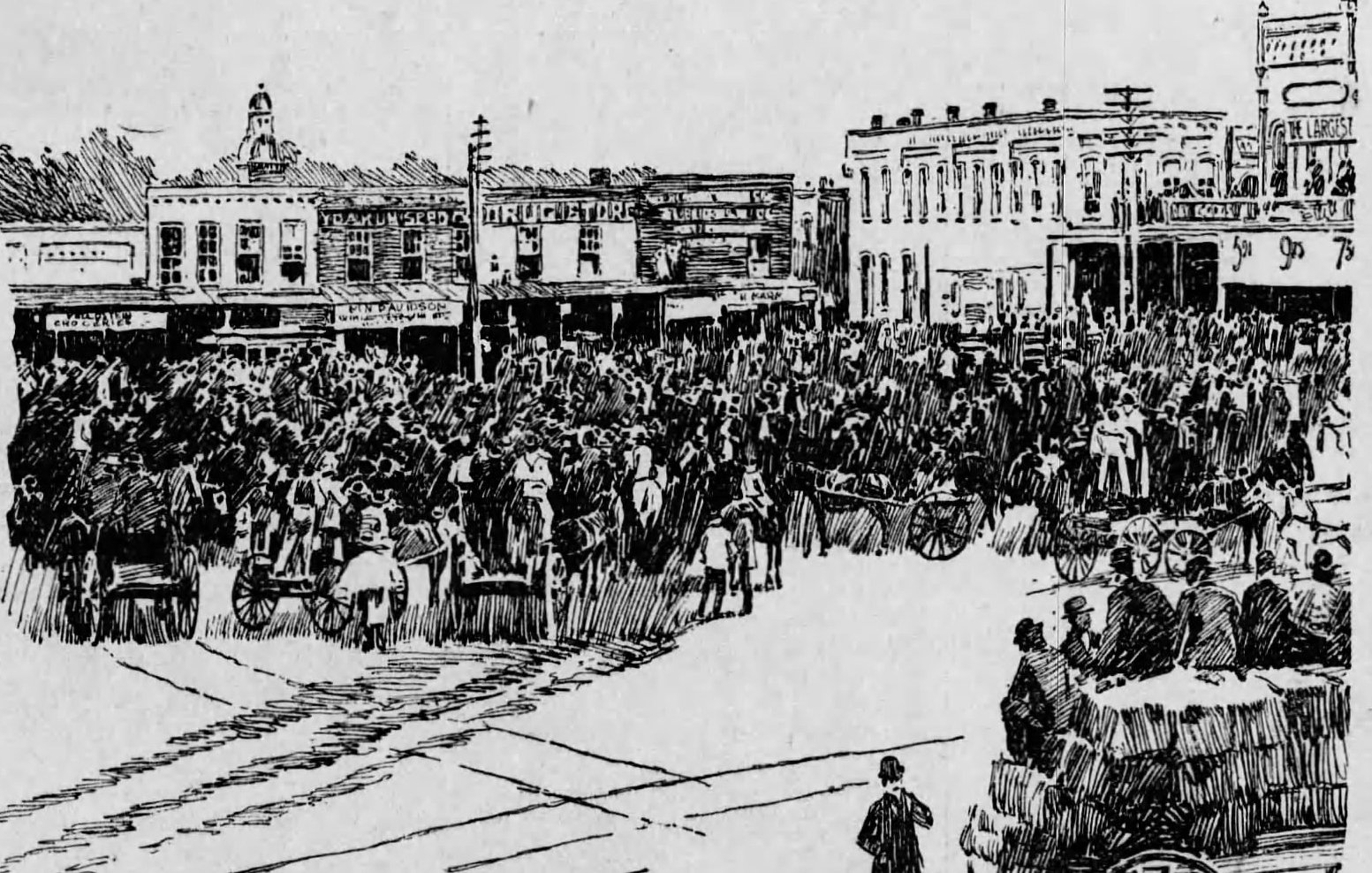

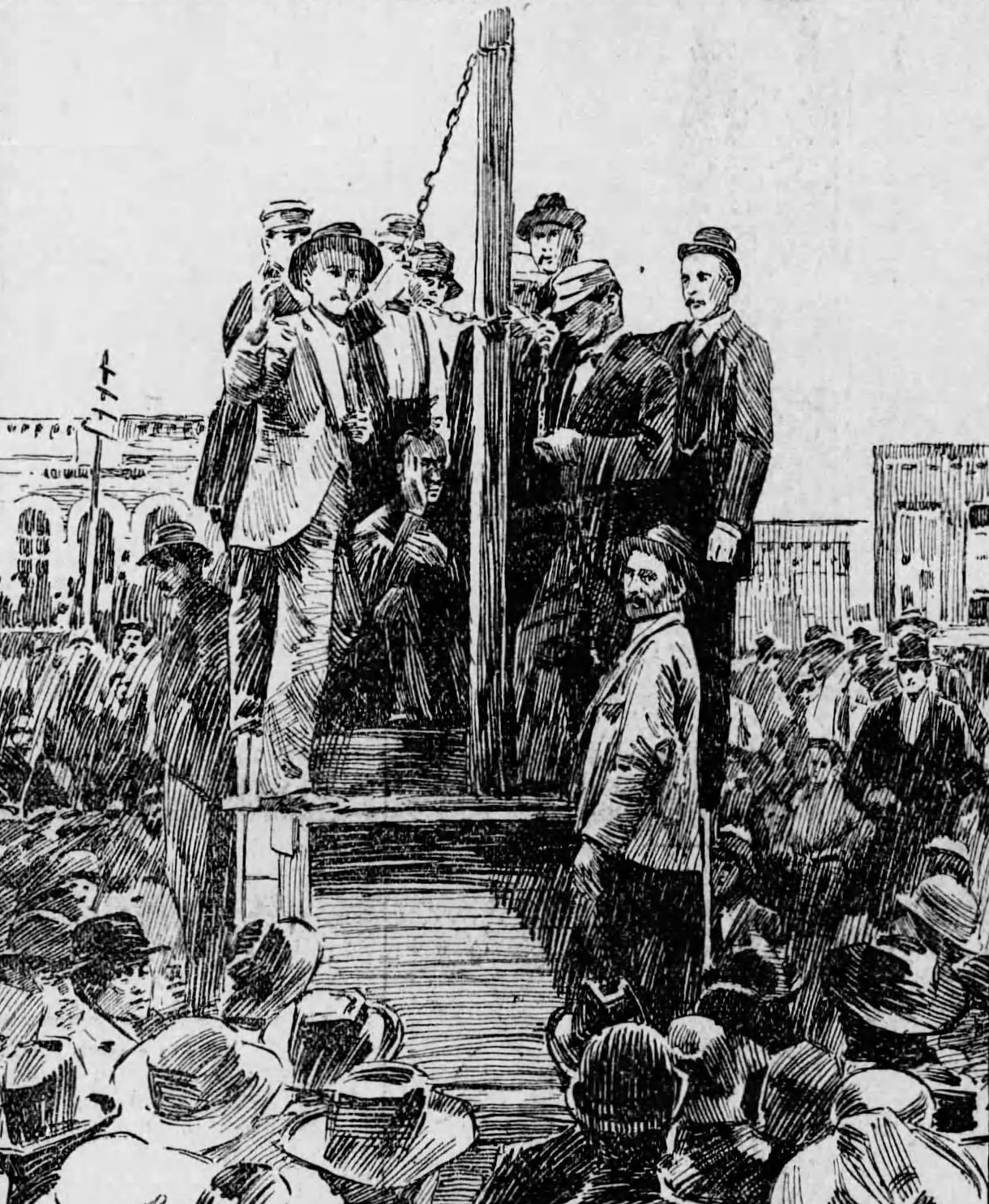

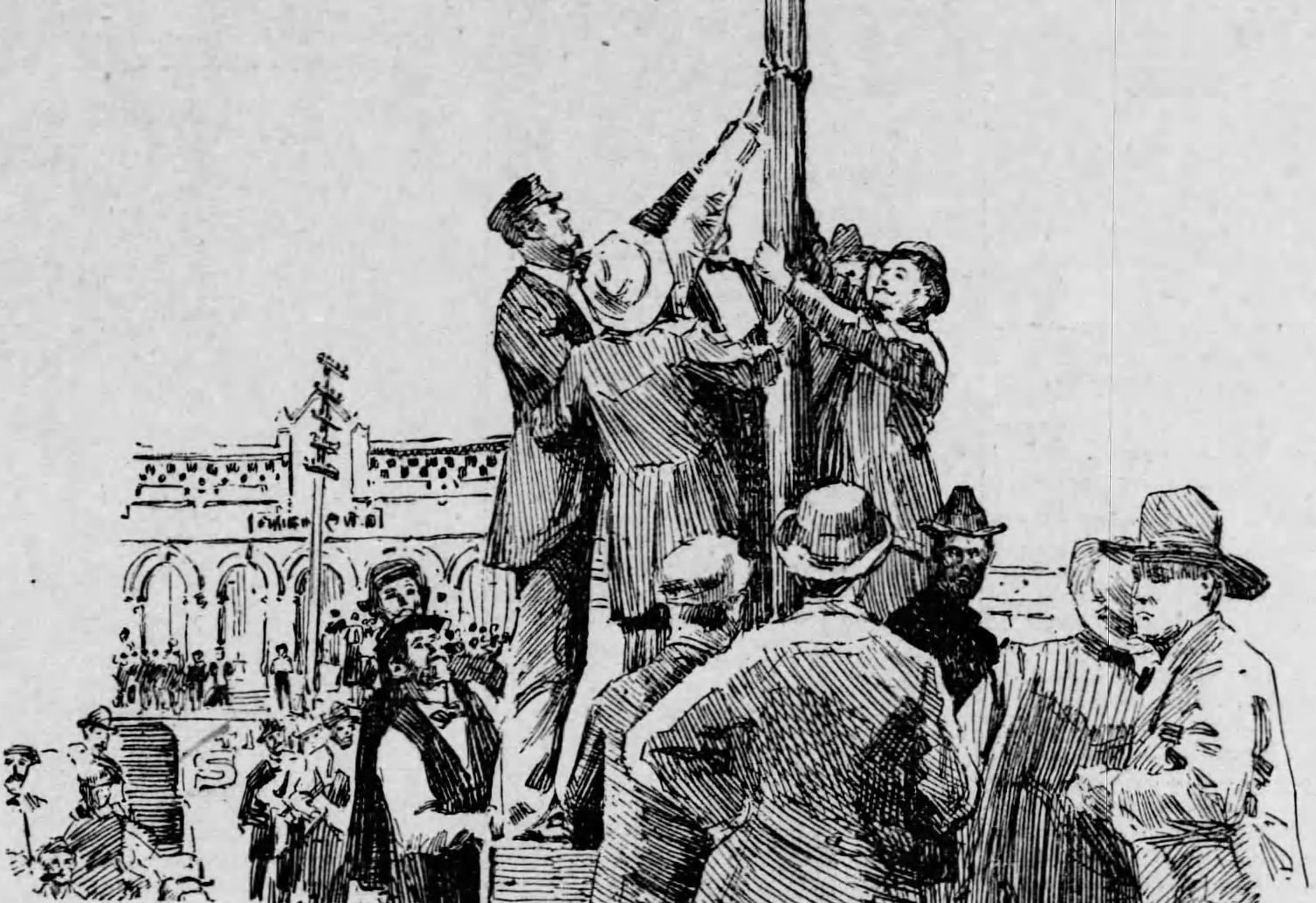

After hearing the confession, the men immediately voted to lynch Hilliard on the square. The mob was aware that large crowds were already gathered for the Barnum and Bailey’s Circus the following day. The posse arrived downtown with Hilliard in tow at 4 pm to a mass of eagerly awaiting people. Within the hour, an improvised scaffold was built using materials used in the construction of the new courthouse, and supplies of wood, straw, and coal oil were also gathered. A few moments later, Hilliard was taken to the platform and given a chance to say his final words. After being afforded the luxury of prayer, the mob then tied Hilliard to an iron rail and raised him over the crowd.

It was one of the largest lynch mobs in Texas history to gather to witness ritualized racial torture.

Mr. Bell arrived on the scene, lit matches then threw them on the kindling. Hillard was immediately engulfed in fire. The crowd lit their own little “missiles” to throw at the victim. The murderers then doused the fire only to relight it a short time later. The mob repeated this cycle to extend the torture heartlessly.

Hillard begged for mercy, but none came. This cycle of brutalization happened a few times more before Hillard began attempts to swallow the flames and beat the back of his head into the iron rail, attempting to end his suffering.

One source wrote, “Hilliard’s power of endurance was the most wonderful thing on the record. His lower limbs burned off before he became unconscious, and his body looked to be burned to a hollow. Was it decreed by an avenging God as well as an avenging people that his sufferings should be prolonged beyond the ordinary endurance of mortals?”

Tylerites wrongly thought that God endorsed this trial by literal fire.

The funeral pyre and Hilliard’s physical form were all reduced to brittle cinder. Reports went out that the circus could not top the slow roast of Henry Hillard the night before. According to E.R. Bills, author of Black Holocaust: The Paris Horror and a Legacy of Texas Terror,

“The prevailing white sentiment regarding Hillard’s fate was conveyed in the November 1 edition of the Fort Worth Daily Gazette: The work of burning the negro was not done by any mob of infuriated men, but by the best citizens of East Texas, coolly and deliberately. The governor of the state, in the performance of his duty, was [is] compelled to follow the mandate of the law and have an investigation made and an attempt made to apply the law. These people will fail. Smith county officers did all in their power, but they were toys in the hands of 10,000 people.”

Later, Breckinridge-Scruggs Co attempted to make a profit selling pictures and postcards of the grisly event. They wrote in their advertisements, “We have sixteen large views under powerful magnifying lenses now on exhibition. These views are true to life and show the Negro’s attack, the scuffle, the murder, the body as found, etc. With eight views of the trial and burning. For the place of the exhibit, see street bills. Don’t fail to see this.”

Newspapers throughout the nation printed sketches of the photos. Ministers spoke out against the brutality of the lynching. But there is no record of any repentance for the injustice.

Note: A set of the stills is currently stored at the Library of Congress.

“Such brutally violent methods of execution had almost never been applied to whites in America. Indeed, public spectacle lynchings drew from and perpetuated the belief that Africans were subhuman—a myth that had been used to justify centuries of enslavement, and now fueled and purportedly justified terrorism aimed at newly emancipated African American communities.”

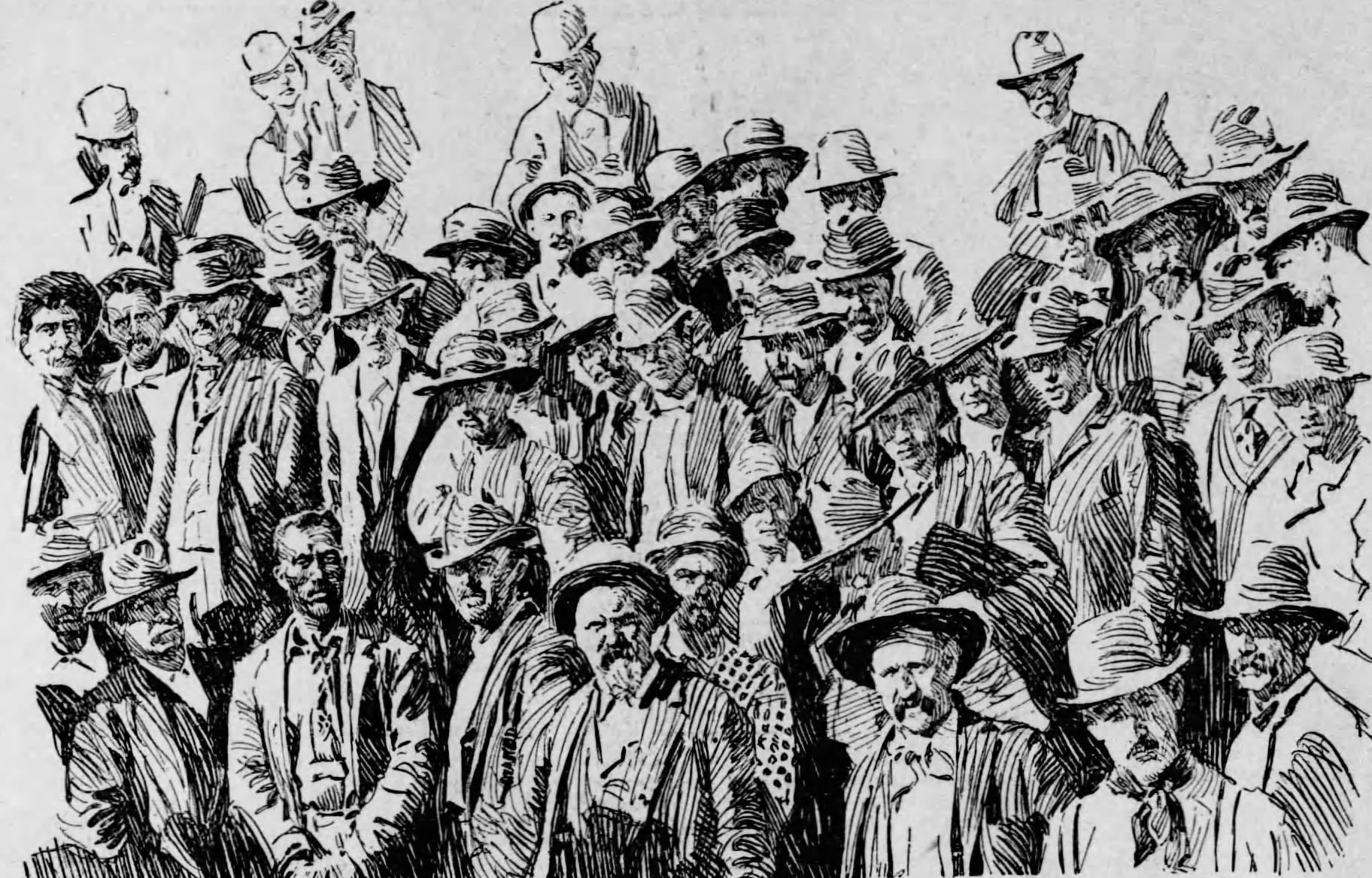

The below images are taken from a stereograph by Tyler photographer C.A. Davis whose Iron's Studio was located on North College St. The images, in order, show Robert Henson Hilliard surrounded by a mob before being burned in Tyler, Texas; he was accused of raping and murdering a white woman. The first photos in the set, though, are a recreation by actors and contain a primitive attempt at adding color. The images above are wood engravings of the Davis photos, published nationwide. These were specifically taken from San Franscio’s The Examiner., November 15, 1895.